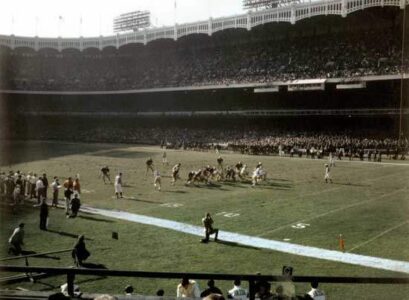

It’s an iconic football image: the aftermath of a devastating blindside tackle executed at full speed. November 20, 1960, the game in its final minutes, players and coaches on the sidelines wrapped in parkas against the late afternoon chill. The victim, New York Giants’ 30-year-old running back Frank Gifford, lies supine and unconscious on the Yankee Stadium turf, having just suffered a concussion that will cause him to miss the next 18 months of football. The perpetrator, Philadelphia Eagles’ 35-year-old linebacker Chuck Bednarik, known as “Concrete Charlie,” stands celebrating over him, hips twisted, fist cocked in triumph.

For the last 56 years, stories about either of these two Hall-of-Famers routinely referred to the collision. It’s not just a defining moment for the way the NFL is perceived, it’s also a defining moment for the way Gifford and Bednarik are perceived. Despite long and distinguished careers during and after their playing days, Gifford is the player who got brained, Bednarik is the player who brained him, and such collisions are the essence of the sport. As Gifford later wrote in his book The Glory Game, “Professional football had speed and it had brutality,” and the sport’s violence was just as compelling as its speed and grace. “The hits, the man-to-man contact that echoed into the rafters — all interwoven with the highest level of individual athleticism any sport could offer.”

When Bednarik died from complications of Alzheimer’s disease in March 2015, ESPN.com used the occasion to reflect on the play, describing it succinctly: “Gifford caught a pass over the middle. Bednarik dropped a shoulder into Gifford, knocking the ball out of Gifford’s grasp and knocking him out cold.” These bare facts understate the blunt force of the impact, the suddenness with which Gifford went from blazing forward movement to shocking stillness.

Gifford himself describes it in greater detail in The Glory Game. “I didn’t see Bednarik coming full speed at me from the far side of the field. Bednarik, taking aim, actually turned his head away. There was no helmet-to-helmet collision. There was no clothesline; his arms weren’t even raised. Bednarik’s left shoulder pad hit my left shoulder pad … In a backward free-fall, with no time to cushion myself, my helmet slammed to the hard ground; that caused the concussion.” This latter point, in the macho world of football, is so important to Gifford that he mentions it a second time: “It wasn’t the Eagle linebacker who hurt me. It was the hard, frozen Stadium dirt that did the damage.”

When the New York Times revealed that Gifford, who died five months after Bednarik, had suffered from the degenerative brain disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), they brought up the play in their lead sentence, calling it “one of the most brutal collisions in NFL history.” In obituaries and tributes to Gifford, it was described as “a legendary hit,” “a crushing blow,” “the NFL’s most vicious tackle,” “as famous a concussion as there had ever been in the National Football League,” “a near-beheading,” and “one of professional football’s signature moments.” Bednarik’s teammate Tom Brookshier said, “Chuck knocked him right out of his shoes.” Gifford’s teammate Sam Huff said, “I thought Bednarik killed him.”

Football’s characteristic violence, its sanctioned mayhem and head trauma, combine in this image with the very human story of two men in their professional primes, both of whom will eventually develop degenerative brain diseases, their lives twined like a double helix, part of football’s DNA.

The hit is one of those enduring sports moments, like Willie Mays’ great catch in the 1954 World Series, that an impossible millions of people claim to have witnessed in person. I know of three people who actually did.

One — if his classic 1968 fictional memoir, A Fan’s Notes, is to be believed — is the writer Frederick Exley. The book’s climax occurs as Exley watches the famous play unfold before his eyes at Yankee Stadium. He sees Bednarik “coming from behind Gifford out of his linebacking zone, pounding the turf furiously, like some fierce animal gone berserk.” He knows Gifford is unaware of the danger and helplessly whispers “Watch it, Frank. Watch it, Frank.” The scene is like “watching a tractor trailer bear down on a blind man.” Exley describes the hit accurately, Bednarik’s shoulder meeting Gifford’s chest and neck, “taking Gifford’s legs out from under him, sending the ball careening wildly into the air, and bringing him to the soft green turf with a sickening thud.” Carried off the field on stretcher five minutes later, Gifford looks “like a small, broken, blue-and-silver mannikin.”

Exley’s reaction to having seen this is shattering. “In that limp and broken body against the green turf of the stadium, I had had a glimpse of my own mortality.”

I had a very different reaction. I was there at Yankee Stadium with my uncle Al, the tickets a gift from him in honor of my bar mitzvah two months earlier. At 13, I was an avid football fan, Giants fan, Gifford fan just waiting till next year, when I could finally play for my high school’s freshman football team. Gifford had even lived for a while in Long Beach, New York, the small barrier island off the south shore of Long Island where I lived, too, after moving from Brooklyn three years earlier. There was nothing Uncle Al could have given me that I’d have appreciated more. Our seats were just above the passageway into the Giants’ dressing room, and I remember watching Gifford pass directly below me as he was being carried off the field on a stretcher. I knew with absolute certainty that, though things didn’t look promising for him right now, he would recover and be his old self before long. He’d just had a nasty ding, I believed, just had his bell rung, the kind of thing that happens all the time. Playing football means getting back up from these kinds of hits and playing through injury. I understood that and looked forward to proving myself. Sure, Giff might not return to this particular game since it was already deep into the fourth quarter, but he’d play soon, running the ball again, catching the ball again, taking his hits again.

For the next few years, as I read football magazines, I’d cut out pictures of my favorite players and taped them to pieces of cardboard, creating my own football cards. I played games with them on the bedroom floor, running and passing, making tackles; Gifford’s card was the most worn from overuse. Only a few months earlier, I’d created a card with my own picture on it. In my imagined games, Floyd Skloot and Frank Gifford shared the Giants’ backfield, and in those games I began readying myself for next year’s freshman games. I blocked for Gifford and he blocked for me. He threw passes to me on surprise plays of my own design. Seeing Gifford carried off the field, I promised myself that next year — in his honor — I would play the way he played, the way we both had played on the floor of my room.

I did ready myself mentally. I visualized touchdowns, first downs, open field tackles, saw myself intercepting passes, fielding kickoffs, diving to make catches. I read articles about football in SPORT magazine, including one about Chuck Bednarik. I wanted to represent our small island city well on the field, go off the island with my teammates and take on the bigger schools. I also readied myself physically, running on the boardwalk and beach, doing calisthenics, lifting weights.

But I neglected to grow. At 14, I was in the middle of a “growth spurt” that would eventually leave me at my adult height of 5’4″. But I wasn’t quite there yet. In the fall of 1961, when I joined the Long Beach High School Marines freshman football team, I weighed 135 pounds. But I did win the 40-yard sprint on the first day of practice.

That first day we all lined up before a doctor who examined us quickly. He listened to our hearts and lungs, looked in our eyes and throats, tested for hernias by grabbing our testicles and ordering us to turn our heads and cough. Pronounced fit and safe for contact, we were issued practice gear and learned to put on the girdle of hip and tailbone pads, knee and thigh pads, shoulder pads and elbow pads, mouthpiece and helmets. I loved putting on the gear, suiting up alongside my fellow players, smacking each other on the shoulder pads and helmets. Go Marines! It made me feel protected, invincible, and part of a team of fellow invincibles.

Our playing field behind the school building was on the bay side of the mile-wide island. It was wind-whipped and hard, mostly dirt with a few scraggly patches of grass. I remember when one of our linebackers broke his collarbone while making a tackle during practice, his screams were caught up and whisked away in the crosswind. So, too, on blustery days were the quarterback’s calls at the line of scrimmage, forcing us to rely on hand signals and body language.

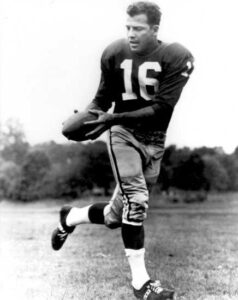

I requested uniform number 16, Gifford’s number. But another player had already claimed it, so I took what the equipment manager offered, 35. When I tucked in the jersey, the bottom half of the number disappeared into my pants. Coach Eaton, who was also my ninth-grade science teacher, called me Billy because, he said, Floyd didn’t much sound like the name of a football player. Go, Billy, go!

When he was home, my brother Phil was like a second coach. He was 22, playing in a Sunday morning flag football league near our old home in Brooklyn, selling pressure-sensitive adhesives and traveling around the east coast during the week. I remember him rushing into the house after a road trip, singing Who put the bomp in the bomp bah bomp bah bomp while he changed clothes, and leading me outside to go over the nuances of a running back’s three-point stance: squat with right hand resting on the ground BUT DON’T PUT MUCH WEIGHT ON IT, left forearm across left thigh BUT NO FIST FOR GOD’S SAKE KEEP THE HAND LOOSE, head up SEE WHAT’S IN FRONT OF YOU, back inclined forward BE READY TO EXPLODE WHEN THE PLAY STARTS. He swatted at a football I held crooked under my arm, training me not to fumble, and threw me dozens of passes to sharpen my catching skills. And he made sure his schedule was free so he could attend my September 16 season opener at Malvern High School, where I’d be returning kicks and seeing action as both running back and defensive back.

The night before the game, Phil took me out for dinner. Steak, he insisted, medium rare. For the protein and the iron and the blood.

Our team bus pulled into the parking lot, and I thought, We must be much too early. No cars, no fans, no marching band or cheerleaders. It was just a freshman game, but surely there should have been some signs of activity, some noise. We were dressed in our game uniforms, chinstraps dangling from our helmets as we got off the bus, cleats clacking on the asphalt. It was a cold morning and as we began trotting toward the field I could see the vapor of our breath. Then Coach blew his whistle and yelled that we had to get back on the bus. We were at the wrong field.

That’s the last thing I remember until I woke up and saw my brother watching television from his bed across our room. There was gunfire and a flicker of light against the lenses of his eyeglasses, as though the pain in my head were being made audible and visible. Then I realized he was watching Have Gun — Will Travel, which meant it was nearly 10 p.m. on Saturday night.

“What happened?”

Phil looked over at me and said, “If you ask me that again I’m going to give you another concussion.”

I realized my head was surrounded by pillows. I licked my lips and discovered a scab on the lower one in the shape of my upper teeth. I tried to sit up and he warned me not to. Doctor’s orders.

“He also said to give your brain a rest. That shouldn’t be hard since you never use it anyway.”

“What happened?”

Phil looked over at me for a moment and decided, I think, that I was finally conscious for real. So he said, “Wait till the show’s over.”

Phil said I’d had the first concussion on the opening kickoff, but no one realized what had been happening to me until he mentioned the sequence of plays to the doctor later. I’d fielded the kick and run about 10 yards before veering toward the sideline and being hit across the helmet by two tacklers simultaneously. Phil said I was so short that I almost ran underneath their outstretched arms. But not quite, and I was like a car that doesn’t make it under the overpass — two forearms to the head. I was very slow to get up, and wobbly, but made it to the bench and was soon eager to get back into the game.

Near the end of the first quarter I tackled Malvern’s huge fullback in the open field, and the collision was so hard my helmet flew off and mouthpiece popped out. Phil said he saw me stagger when I got back up and saw me put the mouthpiece into my rear pocket instead of back in my mouth. In hindsight, he knew I should’ve been taken out of the game then, though I trotted back to my position and seemed to be okay.

The next play ended with a group tackle, me and two other defenders coming together to stop the fullback, and Phil could hear the helmet-to-helmet contact. He said that when I hit the ground I rolled over and spread my arms, remaining still until the other tacklers reached down to yank me back onto my feet. Then I walked a few steps toward Malvern’s huddle before a teammate turned me around. A few plays later, Phil lost sight of me in a pileup on the far side of the field, but I was the last one to get up and was holding my hands up to the sides of my helmet as though in pain. After each tackle I’d been less and less steady, moving, he said, on instinct. Phil started making his way down to the field to tell Coach Eaton I was in trouble, but the next play began before he could get there. He saw what was happening and vaulted the fence as I made a solo tackle and the fullback’s knee smashed under my chin like a prizefighter’s uppercut. I landed on my back and began to convulse. My brother threw himself across my body.

He didn’t know how long the convulsions lasted, but I was unconscious on the field, then unconscious on the stretcher as I was carried into the locker room, and unconscious there for several minutes until I began to rouse, lapsing in and out of consciousness as a doctor arrived. There were, Phil said, probably three or four concussions within the space of 12 or 15 minutes, plus assorted other blows to the head. Later, when I asked what Coach Eaton had been doing while these plays took place, Phil said, “Shouting, Go, Billy, go!”

I didn’t fully regain consciousness until that night, in our room, near the end of Have Gun — Will Travel, about 10 hours after going into convulsions.

The brain is softand spongy, like pudding or cheesecake. It’s enclosed in three thin layers of tissue to protect it from the skull’s hard shell and floats in a bath of cerebrospinal fluid. Though this structure sounds — and is — fragile, we tango and cartwheel and swan dive and perform an astonishing range of physical activities without sustaining brain injury. But, as Jeanne Marie Laskas writes in her book Concussion, “If you hit the head hard enough, that brain is going to move,” and when it does, “It goes bashing against the walls of the skull.”

Such violent jarring causes the brain’s delicate axons, the neural fibers that transmit messages across synapses, to stretch or twist or tear, short-circuiting those messages. In response, a cascade of neurochemicals is released, further compromising and shutting down normal function. Afterward, the brain struggles to heal itself, and to do so it needs to be protected from additional disturbance. As Laskas notes, “Once you got one concussion, you were more likely to get another. After several concussions, it took less of a blow to cause the concussion and a longer period of time to recover.” In a mild or Grade 1 concussion, victims may be disoriented and confused, lose memory or balance. Severe Grade 3 concussions result in loss of consciousness.

That’s what happened to Frank Gifford. It’s also what happened to me. And it happened to me at the end of a concentrated sequence of lesser concussions and subconcussive hits. “The kind of repeated blows to the head sustained in football,” Laskas writes, “could cause certain and specific debilitating brain damage in certain and specific regions of the brain.” It didn’t have to happen often for there to be lasting damage, but when there were multiple concussions, there was a far greater risk for additional and more enduring harm. There was also a risk that the brain would never fully heal, that the cumulative effect of multiple concussions might be permanent, or that consequences such as depression, behavioral change, shattered memory function, and dementia would develop in the future. According to Bennet Omalu, the pathologist who discovered and named CTE in football players, “The risk of permanent impairment is heightened by the fact that the brain, unlike most organs, does not have the capacity to cure itself following all types of injuries.”

Football’s head hits, particularly those occurring like mine in the open field — on kick returns or downfield tackles where participants move at greater speed — are often astoundingly forceful. In League of Denial, their book about the NFL and concussions, Mark Fainaru-Wada and Steve Fainaru write about the magnitude of violence involved when players were concussed. “For 15 milliseconds, their heads were struck with 70 g to 126 g forces.” The momentum transferred in such a collision is “the equivalent of being hit in the head by a 10-pound cannonball traveling at 30 miles per hour.”

Of course a hit like this will cause havoc. But the lesser, subconcussive hits can also be devastating. Particularly multiple hits before the brain has recovered. Particularly in young, still-developing brains, which are more susceptible to injury than adult brains and take more time to heal. In addition, as Linda Carroll and David Rosner write in The Concussion Crisis, “The young brain is especially vulnerable while it’s healing.” A second injury before it’s had time to heal fully can lead to “catastrophic consequences.”

A month aftermy concussions, I biked across the island to meet friends for a basketball game at the Clark Street playground. My balance still was unreliable, I had a basketball under one arm, and at the entrance to the playground I fell head first — with my bike following — 20 feet into Walter Hagen canal at low tide. Our family doctor, after diagnosing another concussion, put his index finger under my chin and leveled my gaze at his. “What next?” he whispered. “Look, Floyd, don’t even sneeze for the next six months, all right?”

It never occurred to me that I shouldn’t go out for the varsity football team the following year. That I was at increased risk for further brain injury, that I was too small to be playing football and should be running cross-country instead. By September 1962, I was 5’4″ and 140 pounds, confident that by changing my uniform number to 23, I’d left my injury misfortune behind.

I just wanted to play. I can think of endless explanations for why I was so compelled — to prove myself, to demonstrate that I was not too small to be out there with the bigger guys, to court the pain and show myself that I could handle it, had genuine courage. To fulfill my pledge to Frank Gifford. But I never really gave a thought to my reasons. Or to the future, though I knew I wasn’t going to be able to play in college. All I was aware of was the allure of the sport and of the team. I especially loved being the kick returner, on my own near the end zone with the whole field spread out before me, running at top speed before anyone could reach me. I didn’t know and wouldn’t have cared that, as Gregg Easterbrook says in The King of Sports, his book about the need to reform football, “Kickoff returns produce more concussions per play than any other action in football.” Besides, most of the damage was done by my reckless play as a defensive back, hurling myself at the much larger players who were carrying the football.

Looking back across 54 years, I realize how lucky I was that I broke my thumb early in my sophomore season and was unable to play again that year, and broke two ribs early in my junior season — and broke them again preparing to return to action — and was unable to play again that year. Otherwise, given my increased susceptibility, I would surely have incurred additional concussions. As it was, I managed to have one more, during a pre-season scrimmage against Far Rockaway High School in my junior year, when an opposing linebacker elbowed me across the side of the helmet after the play had ended. As I lay on the grass, I had no feeling in my hands and feet, then sharp tingling, and had to be helped off the field.

Despite my pleading, no one in my family would grant permission for me to play as a senior. My high school football career ended after I’d played in a total of four games across three seasons. I’d had at least four concussions during those years.

In 2012, as evidence of the connection between football and brain injury grew so irrefutable that even the NFL could no longer plausibly deny it, Boston University’s Dr. Ann McKee, one of the neurologists most deeply involved in research into the issue, told the authors of League of Denial, “I’m really wondering where this stops. I’m really wondering if every single football player doesn’t have this.” She wasn’t confining her concern only to professional players. She also told the House Judiciary Committee that thousands of kids playing football at all levels would eventually develop serious brain damage, including CTE. Her conclusions emerged from studies conducted by researchers at Boston University on the brains of 165 people who had played football in high school, college, or the pros. They diagnosed CTE in 131 (79 percent). Of the 91 brains belonging to pro players, 87 (96 percent) had CTE.

I know I didn’t absorb nearly as many head hits as professional or college players, or even high school players who manage to play in more than four games. I didn’t have collisions with guys like Concrete Charlie Bednarik. But I did have an alarming cluster of concussions during a phase of my neurological life when my brain was still developing. With inadequate healing between them, each subsequent concussion compounded the effects of the others.

While there is no longer doubt about the connection between concussions and enhanced susceptibility to future brain injury, the mechanism by which this occurs is less clear. It’s as though a pathway through the body’s defenses has been opened. The neurochemical cascade produced by a concussion surely plays a significant role, corrupting the normal delicate balance that governs neurotransmission, reducing blood flow, depleting the brain’s defenses and leaving it less equipped to deal with subsequent challenges. “Did the brain really always recover from concussions?” Jeanne Marie Laskas wonders in Concussion. “Could there be a cumulative effect from multiple such injuries to the head?”

This vulnerability, my doctors believe, has implications for what happened to me in 1988, when I was 41and contracted a virus that targeted my brain. I’d taken a flight from Portland to Washington, D.C., and my doctors concluded that human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), carried on the plane’s recirculating air supply, was the likely pathogen. It’s ubiquitous and usually harmless, but also known for its potential neurovirulence in susceptible people. My brain — in part because of the previous injuries to it — couldn’t adequately defend itself. The lesions left by the viral attack are visible on MRI scans and make my brain look like someone stomped on it with their cleats.

In a sense, football had become an organic part of me when I was a teenager, my concussion history never fully resolving though I’d been away from the game for 52 years, neuro-susceptibility a lasting legacy of those four games on the field. After the viral attack I couldn’t read with comprehension for a year, couldn’t drive for six years, couldn’t walk without a cane for 15 years, and am still showing flagrant deficits in such cognitive functions as abstract reasoning, memory, and word finding. My manner of speech is like talking with a limp — I don’t exactly stutter or stammer but I don’t speak smoothly either, my sentences lurching and hitching along as I search for words, lose thoughts, forget questions, sense my ideas free-falling into the silences. It’s one of the areas where my mostly invisible brain damage reveals itself publicly.

In retrospect, it seems fitting that I sustained my latest brain injury — viral, this time — during the fall: football season. In the first, most acute weeks and months of my illness I spent most of my time either in bed or in the living room recliner where I watched television, slept, and leafed through copies of People magazine without being able to retain anything. That was the winter of the infamous “Fog Bowl,” a New Year’s Eve playoff game between the Philadelphia Eagles and the Chicago Bears at Soldier Field, when a dense fog made it impossible for the commentators, fans, and even the players to see what was happening on the field. As I watched, I remember having the same reaction I had when I woke up from my first concussion while Phil watched Have Gun — Will Travel: What was happening inside my head — fog, this time — was being made visible on TV.

I no longer watch football. As the game grew faster and ever more violent, as the players grew larger and what Frank Gifford called “the man-to-man contact that echoed into the rafters” became a featured part of the sport’s promotion, I found myself repulsed rather than compelled. Nearing 70, I found that watching the game or its highlights triggered all the classic fight-or-flight responses — the adrenalin surge, the heart rate acceleration, the unsteady hands. It was just too distressing to know what these hits could do. I believe the consequences still reverberate in my own aging rafters.

As I was preparing to write this essay, I watched the movie version of Concussion with my wife. In slow motion, the film’s final images show a high-school running back breaking through the line of scrimmage and a much smaller, speedy defensive back charging toward him for the tackle. It’s almost an exact reenactment of the play that caused my convulsions in 1961. As soon as the scene began, before it became clear what was about to happen, my wife said that I bolted from the couch saying, “Oh no, oh no,” and stood before the screen wide-eyed, watching the gruesome finale.

Floyd Skloot is a poet, creative nonfiction writer, and novelist whose work has won three Pushcart Prizes, a PEN USA Literary Award, two Pacific NW Book Awards, and two Oregon Book Awards. His latest novel is The Phantom of Thomas Hardy (University of Wisconsin Press, 2016). Reprinted from Harvard Review, a biannual literary journal published by Houghton Library at Harvard University.