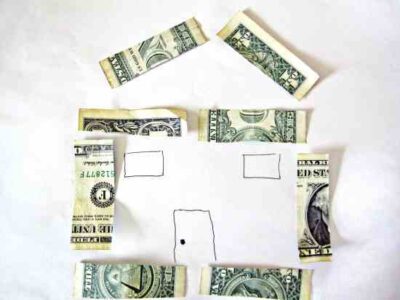

From California to the New York island, private banks are finding ways to swindle the American people. Collateralized debt obligations and asset-backed securities helped create the housing bubble. Wall Street’s 2008 crash continues to reverberate across the nation. Now, bankers are using interest-rate swap bonds to obtain greater profits from loans that finance our national infrastructure, writes Willie Osterweil for Shareable (October 30, 2012).

In this complex process, when a city needs cash for a new school or subway line, Wall Street entices it into a “swap bond” with a promise to pay more (in regular installments) as interest rates rise, while the city pays a fixed monthly rate. But if interest rates fall, so do the bank’s payments, leaving the city scrambling to pay the monthly bills with less cash on hand. In an article for Counterpunch (March 15, 2012), Darwin Bond-Graham wrote that “virtually all interest rate swaps between local and state governments and the largest banks have turned into perverse contracts whereby cities, counties, school districts, water agencies, airports, transit authorities, and hospitals pay millions yearly to the few elite banks that run the global financial system, for nothing meaningful in return.”

One possible solution is the creation of public banks. These have “a public interest mission, are dedicated to funding local development, and plow profits back into the state treasury to fund social programs and cover deficits,” writes Kelly McCartney in another Shareable piece. Currently, North Dakota’s state bank is the only one in the United States, but Public Banking Institute director Mike Krauss says it “has proved so enormously successful that now 20 states and a growing number of municipalities are taking steps to embrace this model of public finance.” In addition to preventing predatory financial deals, the Bank of North Dakota demonstrated its ability to respond to natural disasters when it loaned some $75 million to flood relief efforts in 1997, reports McCartney.

Surprisingly, the public-banking solution seems to be popular across the political spectrum, writes Osterweil. While Democrats might seem the obvious proponents, Republicans like Krauss prefer a local solution and local control when it comes to solving our nation’s big-banking crisis.